The heptagon puzzle

A few episodes of Wrong But Useful ago, Dave posed the problem:

A regular unit heptagon ((a seven-sided shape where all the angles are the same, and all the sides are 1 unit long)) has two different diagonal lengths, $a$ and $b$. Show that $a+b = ab$

Unusually, I didn’t blog a solution. Sorry about that.

A hat-rack trick

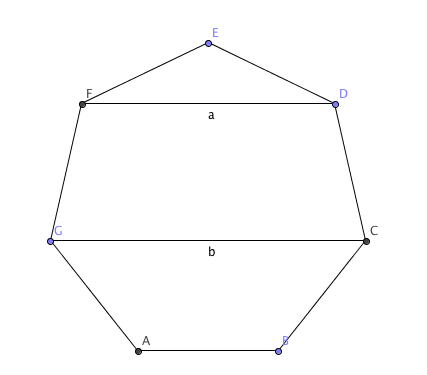

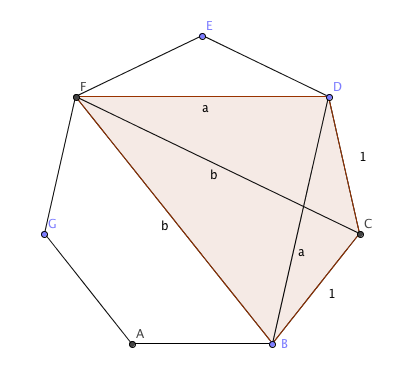

I’ve come up with two approaches, but wanted to showcase one by [twit handle=’notonlyahatrack’] (who is Will in real life) first. He spotted that you can make a cyclic quadrilateral from any four of the corners, and that you can pick the corners so that the sides are (in order) $1$, $1$, $a$ and $b$, as shown here:

He then uses a circle theorem I didn’t know, but probably should have: Ptolemy’s Theorem for cyclic quadrilaterals, which states:

The product of the diagonals of a cyclic quadrilateral is equal to the sum of the products of opposite sides

In the picture, that means $|CF|\cdot |BD| = |CD|\cdot |BF| + |BC|\cdot |BF|$, or $ab = a + b$, as required.

Very elegant! While it’s perfectly legit, I didn’t know Ptolemy’s theorem, and had to resort to other methods.

Similar triangles

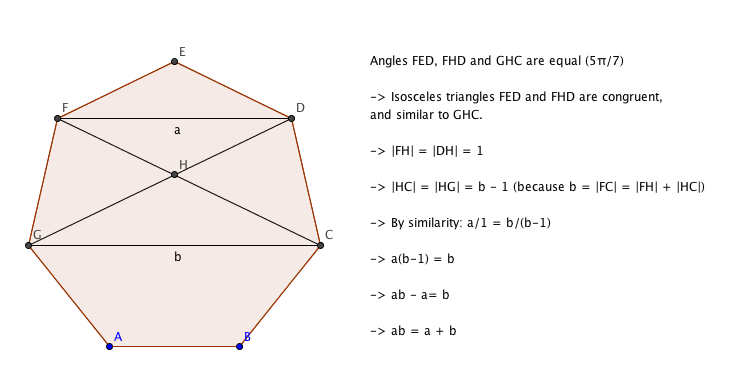

My first stab looked like this:

Looking back, it wasn’t entirely obvious that triangles FED and FHD were congruent (although they are) - this is because the angle $F\hat D E$ is the same as angle $F \hat G D$, because $FC$ and $ED$ are parallel.

Cosine rule

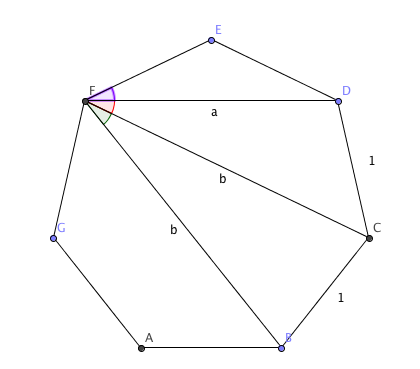

There’s another reason the angles are the same, too: it comes down to another circle theorem (the one about the angles at the edge being half the angles in the middle), from which you can prove that the angles between adjacent diagonals and/or sides from any point on a regular shape are the same. That means their cosines are all the same, too.

There are three distinct triangles here:

- $FDE$, from which you can say the cosine of the angle is $\frac{a}{2}$;

- $FDC$, from which you can say the cosine of the angle is $\frac{a^2 + b^2 - 1}{2ab}$

- $FCB$, which tells you the cosine is $\frac{2b^2 - 1}{2b^2}$

Working from $\frac{a}{2} = \frac{a^2 + b^2 - 1}{2ab}$, we get $ a^2 b = a^2 + b^2 - 1$. That rearranges to $1 = a^2 + b^2 - a^2 b$.

Working from $\frac{2b^2 - 1}{2b^2} = \frac{a}{2}$, we get $2b^2 - 1 = ab^2$, or $1 = b^2(2-a)$

Eliminating the 1, we end up with $b^2(2-a) = a^2 + b^2 - a^2 b$. Take away a b^2 from either side:

$b^2 (1-a) = a^2(1-b)$, which expands to $b^2 - b^2a = a^2 - a^2 b$, or $b^2 - a^2 = b^2 a - a^2 b$; some nifty factorising:

$(b-a)(b+a) = ab(b-a)$ - and since $b \ne a$, we can divide by $b-a$ to get:

$b+a = ab$ as required.

There’s probably a way through the algebra that’s a bit quicker, but I’m quite pleased with that one; the Mathematical Ninja would hate it.