A MathsJam Masterclass

At the East Dorset MathsJam Christmas party, @jussumchick (Jo Sibley in real life) posed the following question:

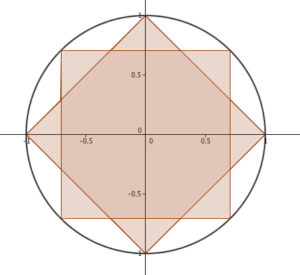

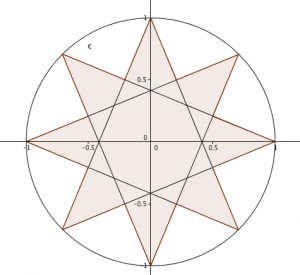

There are two ways to draw a 16-gon with rotational symmetry of order 8 inside a unit circle, as shown. What’s the ratio of their areas?

Typically, I look at this sort of question and sigh: it’s going to need a (shudder) calculator to work out the lengths of the various sides, and the areas will be really ugly numbers… but I was assured the answer was ‘something nice’. So, I put down my mince pie and picked up a pen. (For the sake of narrative, I’ve covered up some of my mistakes.)

Typically, I look at this sort of question and sigh: it’s going to need a (shudder) calculator to work out the lengths of the various sides, and the areas will be really ugly numbers… but I was assured the answer was ‘something nice’. So, I put down my mince pie and picked up a pen. (For the sake of narrative, I’ve covered up some of my mistakes.)

The splitting up of the shape

My first step was to notice that I could split each of the shapes into 16 congruent triangles – from the centre of the circle (O) to a point on the circle (A), to one of the ‘elbows’ (B) between the circle points. In the 16-gon made of two squares, the angle OAB is $\frac{1}{4}\pi$, as it’s half of a right-angle. The angle BOA is $\frac{1}{8}\pi$, because it’s a sixteenth of a circle, and the final angle ABO is $\frac{5}{8}\pi$. In the other 16-gon, angle BOA is $\frac{1}{8}\pi$, like before; ABO is easy to find, too – if you continue OB through B, the other side of the angle is $\frac{1}{4}\pi$ – so ABO has to be $\frac{3}{4}\pi$. OAB turns out to be $\frac{1}{8}\pi$ as well. In each case, the side opposite the largest angle is 1 – the radius of the circle.

An alternative area formula

Every Core 2 student knows what to do from here: work out another side using the sine rule, then use $Area = \frac 12 ab \sin(C)$ to find the areas, multiply them by 16 and get the ratio. Full marks, next question. And a gaping void in your soul, of course, but you don’t lose marks for that. What a mathematician does is, find a formula for the area of the triangle that works directly from the information we have: a side and three angles. It’s not too tricky: the sine rule says $b = \frac{\sin(B)}{\sin(A)}a$, so $\frac 12 ab \sin(C) = \frac{1}{2} a^2 \frac{\sin(B)}{\sin(A)}\sin(C)$ or, if we’re tidy-minded, $\frac {a^2 \sin(B) \sin(C)}{2\sin(A)}$, which has a nice symmetry to it. (Incidentally: I had this formula wrong to begin with; my $\sin(A)$ and $\sin(C)$ were transposed. It smelt funny: there’s no real difference between angles B and C, so it didn’t make sense for them to be divided rather than multiplied).

Now you work out the areas, right?

Nope. Don’t care about the areas. I care about their ratios. If I set up the triangles so that my $a$ is 1 in both cases, I want the ratio: $ \frac {\sin\left( \frac18\pi\right)\sin\left(\frac14\pi\right)}{2\sin\left(\frac58\pi\right)} : \frac {\sin\left(\frac18\pi\right)\sin\left(\frac18\pi\right)}{2\sin\left(\frac34\pi \right)}$ How lovely! We can simplify it immediately by dividing both sides by $\frac 12 \sin\left(\frac 18 \pi \right)$ to get: $\frac{ \sin\left( \frac 14 \pi\right) }{\sin \left( \frac 58 \pi \right)} : \frac {\sin \left(\frac 18 \pi \right) }{\sin \left( \frac 34 \pi \right) }$ Multiply everything through by ${\sin \left( \frac 58 \pi \right)} $ and ${\sin \left( \frac 34 \pi \right) }$ to get: ${ \sin\left( \frac 14 \pi\right) }{\sin \left( \frac 34 \pi \right) } : {\sin \left(\frac 18 \pi \right) }{\sin \left( \frac 58 \pi \right)} $ – and the left-hand-side works out to be $\frac 12$. The right-hand-side… well, I’d understand reaching for a calculator… but you really don’t need to! It turns out that $\cos(A-B) - \cos(A+B) \equiv 2 \sin(A)\sin(B)$, which means you can rewrite the right hand side as $\frac 12 \left( \cos\left( \frac14 \pi \right) - \cos \left( \frac 12 \pi \right)\right) = \frac 12 \left( \frac 1 {\sqrt{2}} - 0 \right)$, so our ration is: $ \frac 12 : \frac 1 {2\sqrt{2}}$, or, more neatly, $\sqrt{2}:1$. What do you know? It was a nice number after all!